Symbiotic Epidermis: Skin, species, and the trouble with being human

The first thing I noticed at Symbiotic Epidermis at Hypha Studios, before the striking visuals, before the whispering canvases and fleshy things rendered in paint, was the skin. Or rather, the obsession with its limits. Skin as border, as threshold. Skin as the ancient, tired metaphor for where "I" end and "you" begin.

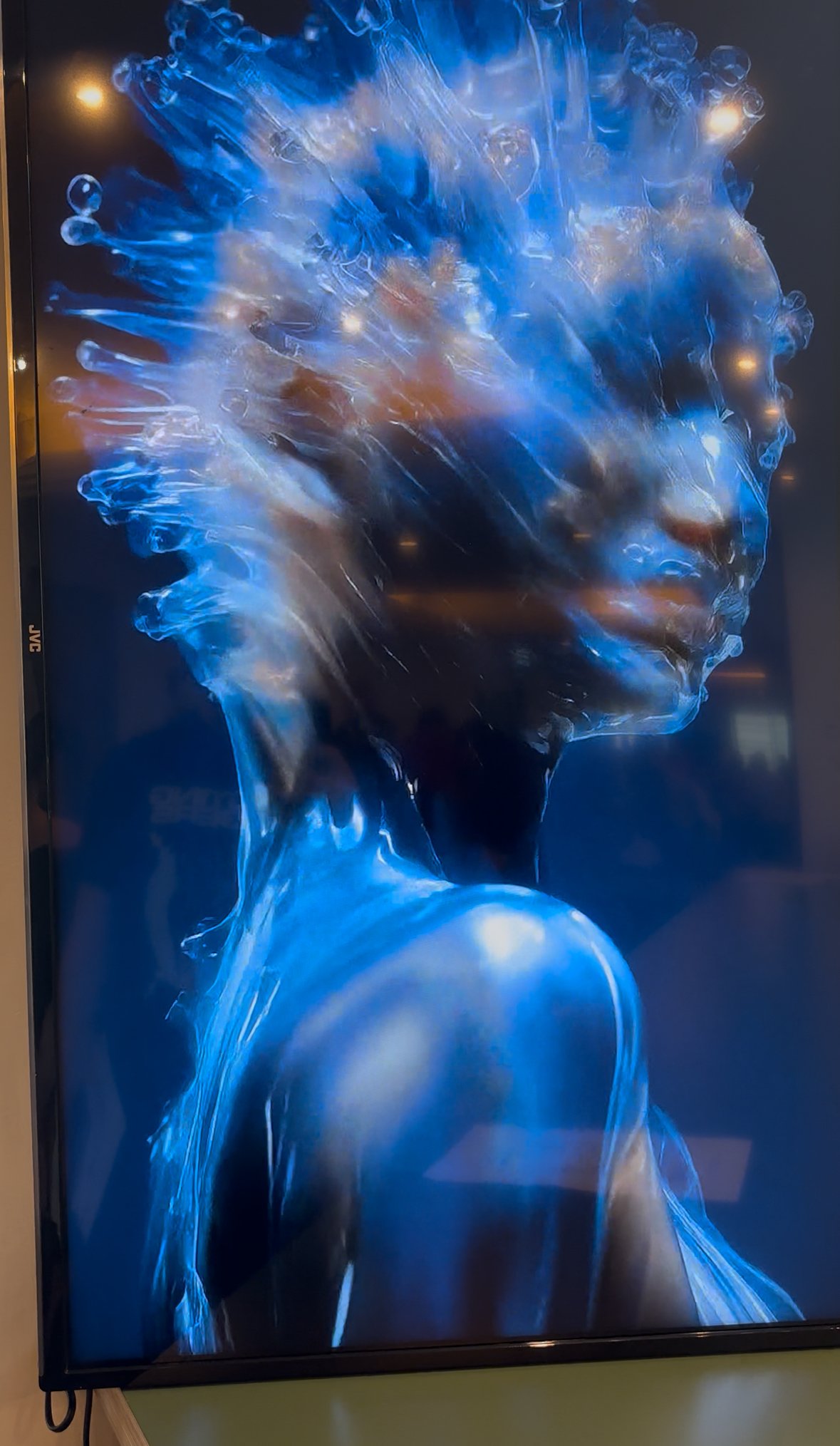

It’s the title’s epidermis, of course, that gives us the clue: not surface, but symptom. The group show, curated by John Angel Rodriguez, is not so much about transhumanism as it is about what we might need to shed, philosophically, emotionally, biologically, if we are to survive what’s coming next.

The base of our intellectual towers

We live, still, in the ruins of humanism. The Renaissance gave us Man (capital M, overwhelmingly white), standing upright in the centre of the cosmos, measure of all things. Modernism inherited his arrogance. Postmodernism deconstructs the above. All our Western intellectual towers are still built on Humanism’s foundations.

Humanism remains the base layer of our civilisational makeup, its values etched deep into our institutions, our law, our language, our machines. Symbiotic Epidermis asks: what if it’s time to evolve? What if we are the skin that must be sloughed?

A rebuke to anthropocentrism

Kamila Sladowska’s work speaks this question in the low frequency of fruits and body parts. Her work - rootlike threads stretching out from a vulva, paintings that could be breasts or fruits, lace containing actual garlic - invites us into a world that mixes nature with the human experience.

This is not nature as a backdrop or resource. It is not Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s noble green to be rediscovered. It is something older, stranger. A rebuke to the anthropocentrism baked into the Western gaze since the Greeks were carving idealised bodies. Sladowska invites us to remember: we are a part of nature, not separate from it. We were always edible.

Rewriting sympathy in the face of strangeness

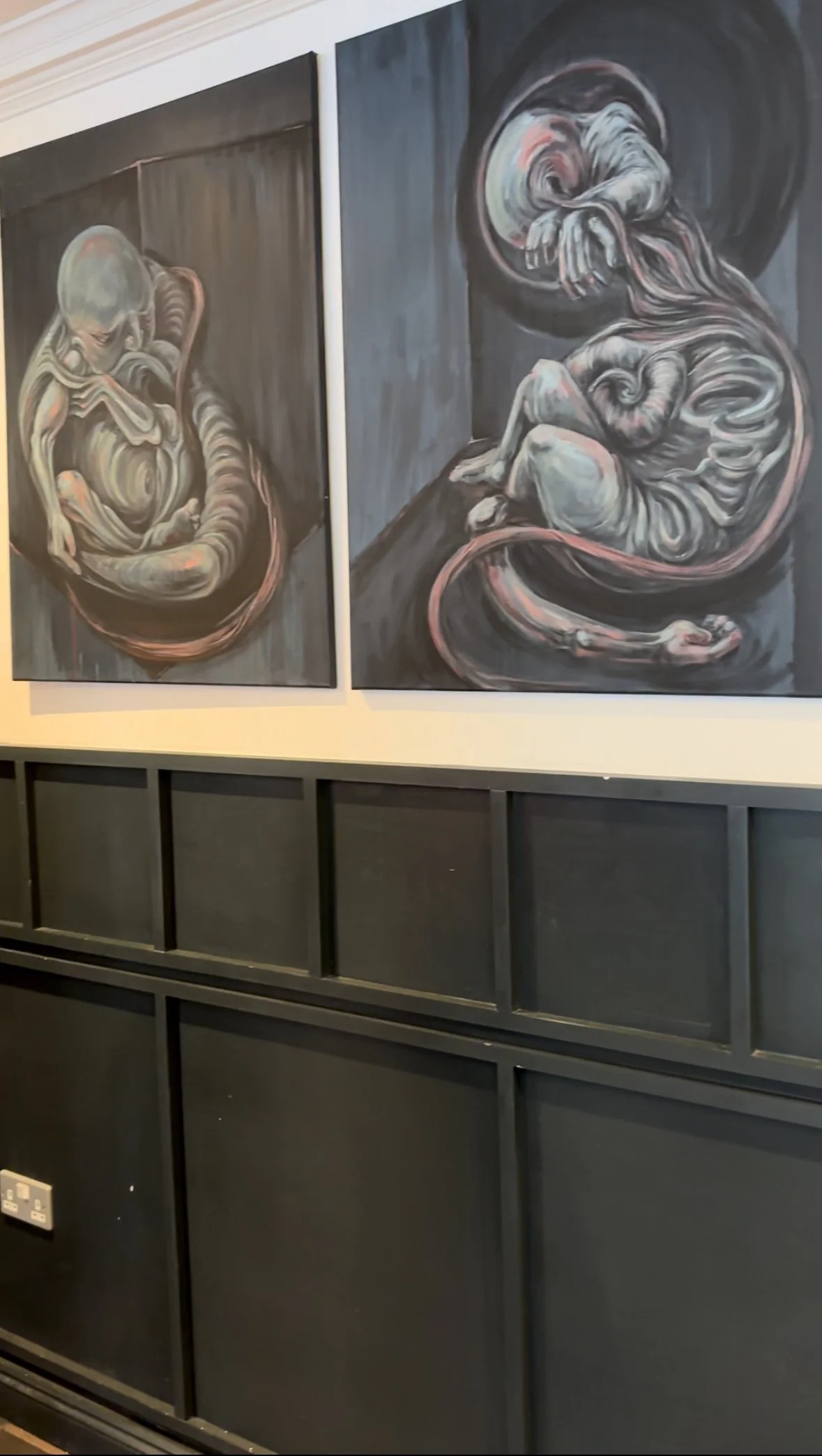

Olivia Bloodworth’s paintings are more unnerving. Her world is not a return to nature, but a confrontation with the other, the alien, the unborn, the soon-to-be. Her palette slithers somewhere between H.R. Giger’s biomechanics menace and Francis Bacon’s screaming mouths.

Yet, despite this horror aesthetic, I found myself feeling for her subjects, embryonic, liminal, caught in their not-yet-ness. She made me care about them, even as they unsettled me. That is an artistic coup: to rewire sympathy in the face of strangeness.

This is the real work of transhumanist art. Not to fantasise about uploading our minds into clouds or grafting metal onto skin, but to expand the field of empathy, across species, across futures, across the unrecognisable. The sublime ruin of Bloodworth’s art act like stage curtains for this moral drama: how to look at something unknowable and still say, you matter.

When the category “human” itself feels unstable

Rodriguez’s curation holds these tensions with clarity and bite. There are many other excellent artists in the show. Rodriguez gives us not a roadmap but a mood, one of philosophical vertigo. What do we preserve of humanism in an age when the category “human” itself feels unstable? Can we keep the dignity without the belief in human supremacy over nature? The care without the centrality?

As I left the show, I found myself thinking not about the future of art, but the future of ethics. What kind of values survive ecological collapse? What sort of empathy can stretch far enough to hold not just other people but the post-human, the hybrid, the unloved? Symbiotic Epidermis does not offer answers, but it makes space for the question: when the skin tears, what grows from underneath?